by Kate MacFarland, US Forest Service, Assistant Agroforester

The Prairie States Forestry Project was an innovative approach to conservation initiated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933 with the goal of creating a “Great Wall of Trees” across the Great Plains. But windbreaks are still an important part of agricultural conservation and community wellbeing across the US, and around the country there is increasing interest in establishing and renovating windbreaks for a wide variety of purposes.

Windbreaks are linear plantings of trees and/or shrubs that reduce wind speed. They protect crops, livestock, structures, and communities. Windbreaks can be designed differently to achieve different purposes. The characteristics that can be altered to achieve different purposes are orientation, length, density, height and continuity. When designed properly, windbreaks can buffer crops from extreme weather and maintain or increase crop yields. They also enhance soil health, produce specialty forest products, and provide other sustainable agriculture benefits. When planted as living snow fences, windbreaks improve highway safety and when planted around farmsteads, they reduce energy costs. They can also be planted as outdoor living barns to protect livestock, as well as to provide a visual screen or reduce odors from livestock operations.

Windbreaks can also be designed to provide habitat, food, and other resources to wildlife, including pollinators. By selecting species for your windbreak that bloom throughout the year, they can support pollinators early in the spring and late in the fall when many other plants aren’t providing nectar or pollen. This habitat can be especially beneficial to producers who grow pollinator-dependent crops.

As in all agroforestry practices, design matters. An improperly designed windbreak can have negative consequences on the area it is protecting. Windbreak designs should reflect landowner or operator objectives and local site conditions.

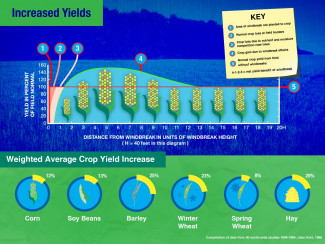

The greatest windspeed reduction occurs in the area from two to five times the height of the windbreak downwind (leeward) side, but extends out to ten times the height of the windbreak. Windbreak publications refer to this as 2H to 10H, with H being the height of the windbreak at age 20. Windbreaks should not have any gaps; they should be continuous. Gaps create a funnel effect that concentrates the wind and can cause damage downwind from the gap. This means replacing trees that die and locating access lanes at the ends of the windbreak is important. Windbreak density is the amount of leaves, branches, and trunks in the windbreak. Windbreak density can be designed to match landowner goals; a denser windbreak allows for greater protection, but a less dense planting creates slightly less protection at a greater distance. Windbreak orientation refers to the direction that the windbreak faces. Windbreaks should be oriented, as much as possible, at right angles to the most troublesome winds. Wind roses help determine seasonal wind direction so the landowner can match the windbreak orientation to the winds that are most problematic. Finally, windbreak length determines the area receiving protection and should exceed the height by at least 10:1.

A wide variety of efforts are being taken across the country to enhance windbreak research, education, and implementation. One such effort began in February 2017, when a team of forestry and agriculture professionals from across the Great Plains met to begin developing a Windbreak Action Plan. Representatives of local, state, federal, and non-profit organizations met in Manhattan, Kansas to lay the foundation for the advancement of windbreak research, outreach, and assistance to support and enhance landowner interest in windbreak renovation, maintenance and establishment. Workshop participants focused on four areas: training for natural resource professionals; outreach and education for landowners/producers; programs and policies to support windbreaks; and critical research.

Another important effort is a Crop/Yield Study being carried out across the Great Plains and Canada’s Prairie

Provinces. Many years of research have documented the relationship between wind protection and crop yields and quality. For example, soybean yields increase 15% when protected by windbreaks and corn yield increases 12%. Fruit and vegetable crops, which can be damaged or desiccated by the wind, also have well documented yield and quality improvements. But some farmers are asking if new crop varieties, equipment, and technologies have replaced the need for windbreaks. This project seeks to collect data from fields with and without windbreaks via the yield GPS-based monitors that many producers have on their harvesting equipment. When analyzed, the yield monitor data will reveal if crop yields change as distance from the windbreak increases. By analyzing multiple sets of data over a period of years from different locations and producers, researchers hope to improve the statistical reliability of the study.

The USDA National Agroforestry Center (NAC) offers resources for planning and design of windbreak systems, as well as resources for training sessions such as sample agendas, presentations, and videos. Visit NAC’s windbreak page to view or order these and other publications or use the windbreak economic tool to estimate costs and benefits. Watch for NAC’s next issue of Inside Agroforestry, which will focus on innovative uses of windbreaks across the US. Sign up to receive email updates or for print publications on NAC’s website.